When building software, we often make key decisions right at the start. Advocates of Evolutionary Architecture will tell you that this is a terrible time to make these decisions – we are at our least informed about our domain, our least familiar with the tools and techniques we’ll be using and our lowest effectiveness as a team. Wrong decisions made at this point often teach people the wrong lesson, driving good developers at successful technology companies into doomed quests to “just get this model right” – refactoring in ignorance instead of getting on with the kind of work that adds value and teaches us how to make good decisions.

Instead, let’s accept our temporary ignorance and optimise our software for changeability so that we can move forward now and change our minds later – when we actually know what we’re doing. To that end I want to share an approach that has helped me in the past – one I’ve borrowed from event-driven architectures and used with great success in a variety of situations. Let’s call it Write Now, Think Later.

Accepting Our Ignorance

A couple of years ago I was working with a bank to deliver a customer-facing web app for tracking the progress of home loan applications. When we arrived, we learned that there was no concept of home loan application status. Home loan applications moved through many different roles and systems, sometimes going backwards or looping around in a complex and poorly-understood process. There were key moments, but people disagreed about what they were and what they meant. Our knowledge of the domain and the systems already in place was poor and we knew it.

The Disaster Waiting to Happen

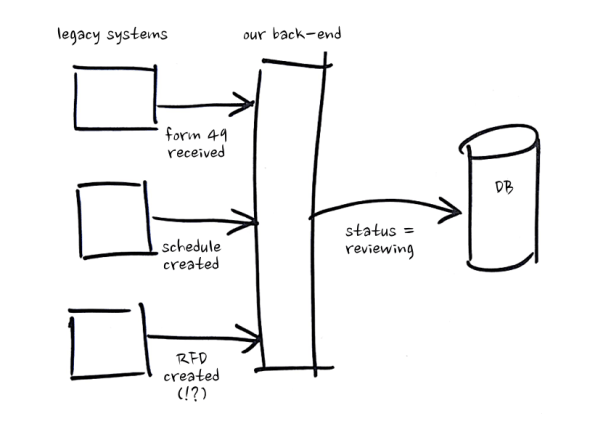

It had been suggested that we approach the problem with something like this:

- Receive inputs from upstream systems

- Determine how each input impacts home loan application status

- Persist updated home loan application status

Given our situation, we didn’t have a lot of faith in this plan. We figured if we went down that road, it would go more like this:

- Receive a bunch of confusing inputs from upstream systems

- Make ill-informed guesses about what they mean and how they impact home loan application status

- Update a mutable data store to reflect our probably-wrong understanding

- Realise we were wrong about what those inputs meant and despair

That all sounded pretty unpleasant, so we went a different way.

Learning as We Went

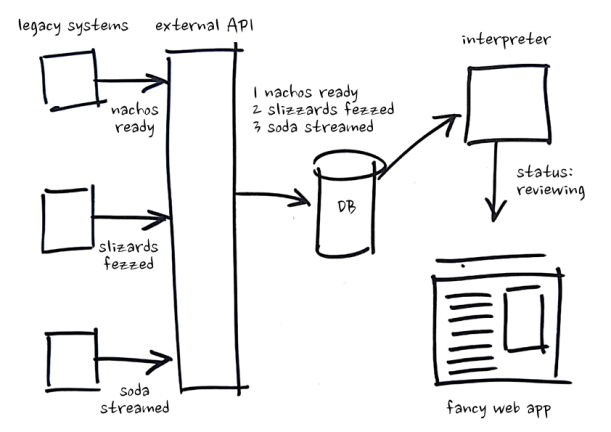

We decided that we would avoid mutating state based on probable misunderstandings of our inputs and instead store these inputs just as they were received – without adding any meaning. This way, we could delay inferring meaning until information was actually required downstream, calculating home loan application status on-demand. Our system ended up looking like this:

- Receive a bunch of inputs from upstream systems

- We don’t know what they mean, but who cares – store them somewhere with timestamps

- Write a service for interpreting these inputs on demand and producing useful information for consumers – we aren’t sure yet but we’ll just make our best guess

- Update that service every time our understanding of the inputs and domain changes – no need to write migrations or grieve lost data

We were really happy with our results – our system gracefully tolerated our misunderstandings, adjustments and reversals. It would be easy to think the lesson here is use events – but we didn’t really benefit from events per-se – we benefited from a strict separation between the inputs we received (Write Now) and the meaning they had in our software (Think Later). This principle is an important part of event-driven architectures (it’s why articles about event-driven architecture tell you to name your events in the past tense – to make sure you’re storing what happened instead of storing what you think those events meant at a particular point in time), but you don’t need to use events to start writing now and thinking later.

We only had a narrow range of allowed technologies with this client, but we didn’t need a stream-processing software platform, just an already-approved-at-the-bank Microsoft SQL Server with a single table and an already-approved-at-the-bank SpringBoot API to interpret the events sitting in the database. If you have a little more freedom, you can build something with less operational overhead using the AWS Serverless Application Model. With a couple of small scripts and a little template, you can deploy (and update) DynamoDB tables, Lambdas for writing and interpreting data and API Gateways for receiving inputs from upstream systems and making interpretations of your data available to consumers.

Changing Your Mind Cheaply

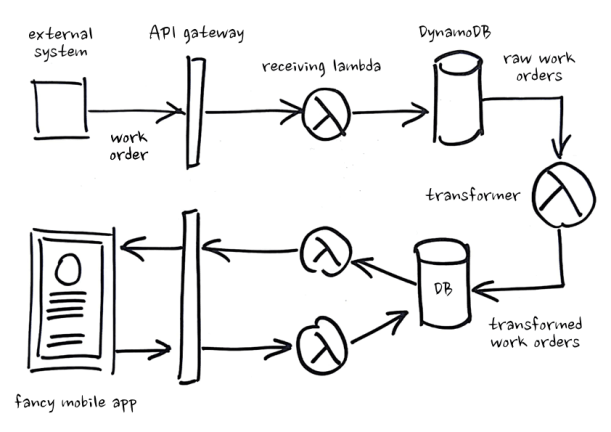

A year later, I was on a different team building field operations and scheduling software. We had one upstream source of information – a legacy system sending us work orders. We received the work orders, transformed them into something that made sense to our application and put the transformed work orders into a table, where we mutated their state as they were completed by technicians. It looked like this:

Getting Stuck

Everything worked fine until we realised we had misunderstood some of the work order data we were receiving. We updated our transformer and had to retransform old work orders and merge in the changes that had been made to those work orders since their previous transformation – but we didn’t know what our changes were! We’d just been mutating our transformed work orders with each change and thereby “pouring concrete on our model” (as a colleague of mine put it). We got through it (a small puzzle for the reader) but it was no fun at all.

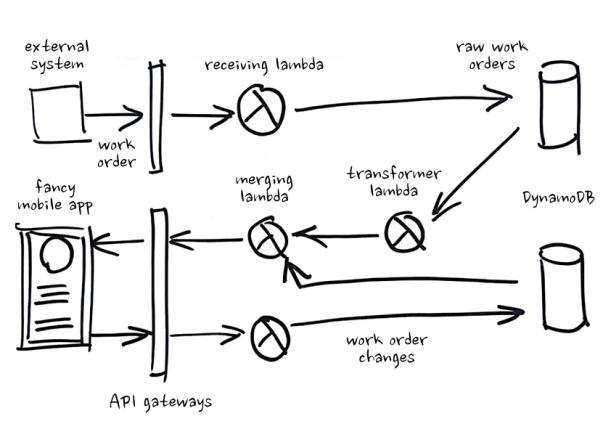

Making Change Cheap

Going forward we knew we could solve our problem with events, but we were too far along and too short on time to redesign our whole system – so we made a simple change:

- We stored our changes separately, instead of mutating state

- We transformed work orders on demand without persisting the result

- We merged changes into our transformed work orders on demand

From that point on whenever we needed to change how we were transforming work-orders, we just changed our transformer and moved on with our lives.

Though we initially performed all of this transforming and merging on-demand, we soon found this wasn’t fast enough for some use cases. Because we were using the AWS Serverless Application Model, it was easy for us to instrument writes to our DynamoDB tables with events and use those events to trigger the transforming and merging of our data asynchronously, storing the results in separate table that could be read quickly and easily by consumers.

We didn’t write any events ourselves, but we were still able to create a strict separation between the inputs we received, the model we presented to consumers and the changes those consumers made. Instead of mutating state based on a point-in-time understanding of how changes ought to impact our data, we wrote everything down as it happened (Write Now) and interpreted it on-demand (Think Later). It worked really well for us and we didn’t need to redesign our entire system to benefit from it.

As in the Back-End, so in the Front-End

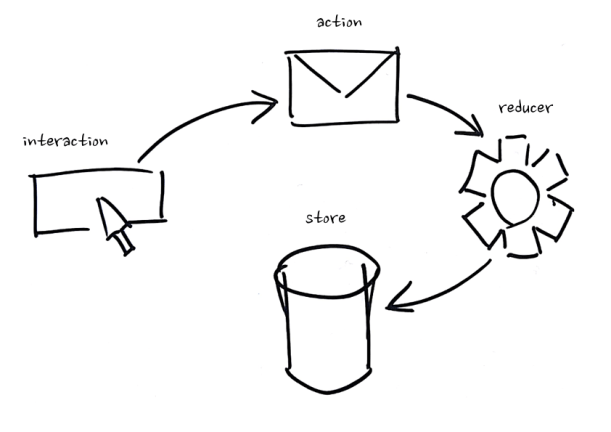

We can also apply Write Now, Think Later in front-end development. Redux makes use of event-driven architectural principles, but many Redux users are missing out on some of the biggest benefits. Redux is tricky and we won’t go into detail here, but the part we care about looks something like:

- Somebody interacts with a component

- An action is dispatched

- A reducer notices that action and mutates data in your store

Missing the Point

I’ve seen many implementations of this pattern where actions are used more like commands – a user clicks a button and a component dispatches an action like SaveBananaForm. That means instead of telling our reducer that the banana form’s save button was clicked, we’re throwing that interaction away and issuing commands based on what we think it means at a particular point in time – we’re thinking now instead of later. If we discover that this interaction actually meant something else, we can’t go back and reprocess it because it’s gone. We know what commands we issued but we don’t know why we issued them.

Applying What We’ve Learned

What if we apply Write Now, Think Later and instead of dispatching future-tense commands as actions, we Write Now and postpone our thinking by dispatching past-tense events as actions – SaveBananaForm becomes BananaFormSaveButtonClicked and we don’t worry about what that means until we get to the reducer.

It seems like a small change, but the accompanying shift in thinking is powerful. Say we initially thought that BananaFormSaveButtonClicked meant we should post that data to the server, then we later realise it actually meant we should validate inputs and only then consider posting to the server. We can rewind our actions and store, modify our reducer based on our new understanding of what BananaFormSaveButtonClicked meant and then playback our actions again. Decisions about what our inputs mean are now easily reversed, keeping our options open and allowing us to move forward without too much analysis.

Key Takeaways

These experiences and others have made me watchful for signs that my team might be building inflexible software:

- Persisting data unnecessarily

- Meddling with inputs before persisting them

- Mutating data instead of saving changes separately

If you’re doing these things too, consider how you can Write Now and Think Later:

- Interfere with inputs as little as possible before persisting them – this way you can change your mind about what inputs mean and how they should be processed

- Consider the inputs you persist immutable and store the changes you make separately – this way you can change our mind about how changes are applied

- Interpret data on-demand where possible – this way adjustments to transformation, applying changes etc. will be automatically reflected in existing data